I know the sidebar says this is “a personal blog with musings on philosophy and politics,” but I could personally do with a break after that last post, so, apologies to anyone confused by the change of topic.

You know what I like? Medium-slow compound time. 6/8 or 12/8, for preference.

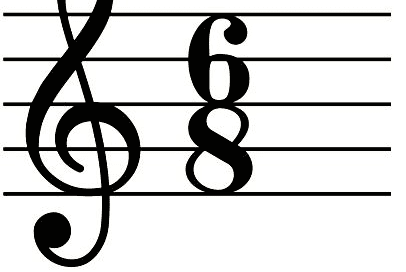

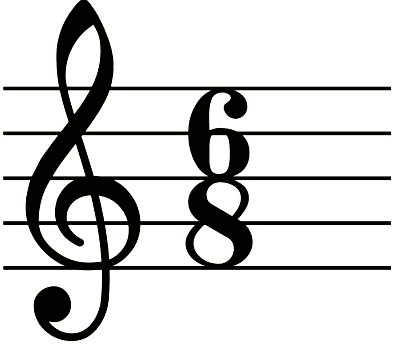

In music, 6/8 and 12/8 are time signatures. The first number tells you how many notes per bar, and the second number tells you what size note each of those notes is. For 6/8, the second number is an eight, so these are eighth notes, also known as quavers. The first number is a six, so there are six beats — or are there?

Well, no. There are six quavers, but there are not six beats. That’s because, almost always, a time signature with a multiple of three over an eight is using what is known as compound time. Instead of having beats that split into halves and then quarters and so on, compound time does its initial beat-splitting into thirds. We do this by saying that a beat is three quavers long1. So 6/8 has two beats per bar: one-and-a-two-and-a.

Similarly, 12/8 has four beats per bar. With or without compound time, two beats per bar or four beats per bar can sometimes be a pretty subtle difference, if any. In both cases, if you slow it down, you can get a nice, measured alternation that sounds like a walk — so much like a walk, in fact, that one musical term for medium-slow is andante, an Italian word that is usually translated as “at a walking pace.”

So, take some slow-walking compound time, and stretch the beats out just enough to make me wait for the next one. Like this:

I Only Have Eyes For You wasn’t originally written in compound time. It was in 4/4, with four perfectly ordinary beats per bar. Then The Flamingos slowed its already-seductive dreamy vibe down a little further, got their accompanying musicians to separate each beat into three, and fitted a swift, soft, feathery “doo-bop, sh-bop” into the first two thirds of a beat in each bar. It’s in 12/8 now, and it will be in 12/8 forevermore.

Who wouldn’t fall in love with a tempo like that? But a slow-walked compound time can do more than just make you sigh. Just four years later, we find Lesley Gore using a slow 6/8 to great effect in You Don’t Own Me:

The early title phrase drifts in, partway through the compound beat. It’s almost casual, maybe a bit tentative. But soon enough this song is hitting its spaced-out beads head on. Its slow walk is a stride.

The light, secondary quavers that make up each beat serve here as contrast for the strong start to each bar, which by the end of the song is hitting with a firm pulse. “I’m young, and I love to be young. I’m free, and I love to be free.” You tell him, Lesley.

There’s plenty of slow compound time in jazz songs from the ‘50s and ‘60s, perhaps because it can blur a little with a swung rhythm. You could restrict yourself to Nina Simone and still be spoiled for choice: Tell It Like It Is, or I Put A Spell On You, or of course Feeling Good, with a brassy bass line that makes Lesley Gore’s stride look like a casual stroll:

In later music, we sometimes find slow-walking compound time used consciously for nostalgia. An Innocent Man, Billy Joel’s concept-album love letter to the 50s and 60s, employs a slow 12/8 in This Night:

Like I Only Have Eyes For You, This Night is a serenade, romantic and dancelike, with soft vocal “shoo-wop” in the background. There is a vulnerability to the uncertain lyrics over the quaver notes in the verse, and Joel stretches it out further by using two verses in a row, making us wait for the chorus. When the chorus does hit, though, it sweeps in like an anthem.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that on an album that includes Uptown Girl and The Longest Time, the gorgeous long phrases of This Night might get comparatively less attention. Still, I often find it hard not to repeat it when it comes by. What can I say? I love a slow-walked compound time.

Mind you, the tempo is not the only thing that catches my attention. Joel’s song-writing ability exceeds his vocal abilities by a fair bit. I don’t mean this as an insult; his vocal abilities are very good. Still, every time I listen to the chorus of This Night, I find myself reflecting that Joel is using the easier way to breathe through a line that long, taking brief breaths in the middle of the phrases so that your ear will skip over the small break. “This night [breath] is mine [breath]/ It’s only [breath] you and I.”

Joel needs that breath after “night” because he hasn’t taken a breath before sweeping into the chorus. It’s a good choice, leading in strong and then shortening the word “night” in a way that complements the rhythm. But that breath after “only” definitely lowers the quality of the phrasing. I’d love to hear the song wihout it. You can’t tell me Karen Carpenter wouldn’t have carried it perfectly, if she could only have had the chance.

Staying with the conscious nostalgia, I had to include this cover by Postmodern Jukebox of No Doubt’s Don’t Speak. Postmodern Jukebox, led by jazz pianist Scott Bradlee, specialises in taking new songs and making them sound old. Vocalist Haley Reinhart is a frequent Jukebox collaborator, and the stylistic range she shows in this piece makes it easy to see why.

Reinhart carries the first verse with free, floating notes that don’t advertise much about the underlying beat. But as we enter the chorus, the accompaniment hits a distinct six-plus-six notes in succession. We’re in 6/8, now! And it works. Where the original song was a shout, this version becomes a full-throated groan. Instead of panicked refusal we have knowing despair.

Partway through, the arrangement tips its hand, launching into an instrumental break with the tune of You Don’t Own Me, just in case you didn’t get the reference. I admit, I wish it wasn’t quite so blatant about it. Yes, yes, very clever and all, but it was more clever when the song was working, on its own terms, in this new format. That’s my opinion, anyway.

Slow-walked compound time doesn’t have to be nostalgic. Sometimes it shows up on its own in a modern context, drawing on those older songs without being beholden to them.

Sara Bareilles has any number of “clapback” songs, aimed at studio executives, or an ex-boyfriend, or just people who annoy her. Machine Gun wouldn’t be a particularly remarkable example, except that it’s in a slow 12/8 and I like that sort of thing. It does some interesting things with its rhythm, too. There are the clipped quavers in the verse, as it details its initial complaint, followed by a drawl on the main beats: “I’m well versed in how I might be cursed, I don’t need it articulated.” There’s that nice bass strut on the bridge, giving a touch of affected cool to Bareilles’ fury. And even as Bareilles decries the rapid-fire criticism she’s receiving, her chorus gives her a rat-tat-tat of her own: “Maybe nobody loved you when you were young… .” The person she’s singing to may not be the only one with a rhetorical machine gun.

Modern production will sometimes obscure the ‘60s roots of a song in slow compound time. On her hit album Back to Black, Amy Winehouse’s beautiful Wake Up Alone is sped up so it no longer exhibits my favoured walking pace. It’s only on her posthumous album Lioness: Hidden Treasures that we get the original recording:

At its original slow pace, with its delicately swung accompaniment, Wake Up Alone’s painful honesty is as quiet and intimate as I Only Have Eyes For You. It holds a heartbreak that is as vulnerable as falling in love. “Pour myself over him, moon spillin’ in … and I wake up alone.”

I can’t leave you all to wake up alone from this piece of writing without giving you something a little more hopeful to end on. Luckily, I’ve kept a final song up my sleeve. The true queen of slow-walked compound time, impressive competition notwithstanding, surely has to be Etta James. At Last is the obvious choice, from her, but will I confess to having a particular affection for A Sunday Kind Of Love:

Etta James plays effortlessly with this song, without ever getting in the way of its delicate wistfulness. The slow 12/8 is dreamy and light and complex, all at once. It’s a hard act to follow, and a perfect note to end on.

You can be declaring your independence, or firing back in an argument. You can be falling in love, or pleading with your love not to leave, or lamenting when your love has gone. Whatever you’re doing, it just sounds cooler in slow-walked compound time.

You could also do this by just explicitly writing each beat of a 2/4 or 4/4 bar as a triplet whenever you want to split it up. In fact, while I don’t have official sheet music for any of these songs, there are certainly online versions of some of them that write it this way. This is generally just a matter of notation, though.

My favorite 12/8 is probably Bach's double violin Largo

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=iSJxZGtzI3s

I believe this is an instance of a

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pastorale

My love for 6/8 and 12/8 comes from the classical world. 6/8 time is great for capturing the rocking motion of a ship on the sea, like in Smetana’s The Moldau (1875) or Chopin’s Barcarolle (1846). 12/8 is harder to find…. Or so I thought, until I just now listened to the chorus of Billy Joel’s This Night for the first time to discover he stole it from Beethoven! It’s the melody of the lovely, anthemic second movement of Beethoven’s Pathetique Sonata (1799), re-cast in modern tones. Sorry if this knocks your praise of his songwriting down a peg, but if it’s any consolation, you’re still spot on with the critique of his phrasing, which doesn’t match Beethoven’s original piano score. While the original was written entirely in 2/4, Beethoven adds motion and nostalgia to the piece by transitioning to an clear (if not literally notated) 12/8 in the latter half.

Sonata Pathetique, Mvmt 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ZK4zTc1HnU