Science rightly impinges on Virtue Ethics

Iris Murdoch, C. P. Snow, Alasdair MacIntyre, and the role of Truth

Iris Murdoch’s philosophical writing, in the manner of a novelist, often contains subtle allusions. Modern academics tend to explain their implications directly, and are so profuse with references that they will frequently include things they haven’t even read. Murdoch, by contrast, will do things like this:

It is totally misleading to speak, for instance, of ‘two cultures’, one literary-humane and the other scientific, as if these were of equal status. There is only one culture, of which science, so interesting and so dangerous, is an important part. But the most essential and fundamental aspect of culture is the study of literature, since this is an education in how to picture and understand human situations. We are men and we are moral agents before we are scientists, and the place of science in human life must be discussed in words. This is why it is and always will be more important to know about Shakespeare than to know about any scientist: and if there is a ‘Shakespeare of science’ his name is Aristotle.

The above quote comes from The Idea of Perfection, an essay (adapted from a 1962 address) whose very title is a subtle allusion, in this case to Descartes—who is mentioned only briefly, and not in the part of the essay that invokes the crucial title concept.

At the time, the “two cultures” reference might well have been transparent, referring as it did to a recent and loud controversy between the sciences and the humanities. But these days, I suspect many readers would be unaware of C. P. Snow’s 1959 address in which he laments the lack of understanding between the “two cultures” of scientists, on the one hand, and literary intellectuals, on the other. One of the most frequently quoted parts of his address is this shot across the bow:

A good many times I have been present at gatherings of people who, by the standards of the traditional [literary] culture, are thought highly educated and who have with considerable gusto been expressing their incredulity at the illiteracy of scientists. Once or twice I have been provoked and have asked the company how many of them could describe the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The response was cold: it was also negative. Yet I was asking something which is about the scientific equivalent of Have you read a work of Shakespeare’s?

I trust the relevance to Murdoch’s statement is obvious! I am almost inclined to view Murdoch’s lack of direct referencing as akin to a deliberate snub, a sort of “We all know who I’m talking about but I won’t dignify him with a direct mention.” Snow’s address was not popular with the literary intellectuals of the time, not least because it began with high-minded language about bridging the gap between two cultures of equal worth, but in its practical recommendations mostly took the part of science against the humanities in a variety of ways.

Unlike Murdoch, I would not cast Aristotle in the role of the “Shakespeare of science.” I mean no disrespect to Aristotle’s important role in the history of natural philosophy, but I dislike the implications of Murdoch’s comment. “So the great edifice of modern physics goes up,” Snow laments, “and the majority of the cleverest people in the western world have about as much insight into it as their neolithic ancestors would have had.” Murdoch’s rejoinder would seem to imply that such a lack of insight would be unimportant, provided that such people understand Aristotle. This is a breathtaking dismissal of the dramatic changes wrought upon our worldview and our understanding of truth over the past several hundred years by the transition of our natural philosophy into what we now think of as “science.”

Murdoch’s initial response to Snow is defensive, and takes a tone of putting science in its place, but I think the subject must have remained on her mind. How does scientific understanding affect our broader worldview? Is it necessary to analyse the perspective of science when constructing a way of understanding, say, ethics?

C. P. Snow certainly holds that science has something to say about morality, because in a 1960 address, entitled The Moral Un-Neutrality of Science, he declares that both the beauty of science and the centrality of truth-seeking to science give the subject an inevitable moral component. Murdoch is Platonist enough that she might agree about the relevance of natural and conceptual beauty to ethics. She also, quite clearly, continued to think about the relationship between seeing truly and acting virtuously. In The Sovereignty of Good Over Other Concepts (1967), she writes:

Of course virtue is good habit and dutiful action. But the background condition of such habit and such action, in human beings, is a just mode of action and a good quality of consciousness. It is a task to come to see the world as it is.

Although Murdoch refuses to ascribe any primacy to science over the arts in this task of truth-seeking, she nevertheless holds that science may be relevant, writing:

Honesty seems much the same virtue in a chemist as in a historian, and the evolution of the two could be similar. And there is another similarity between the honesty required to tear up one’s theory and the honesty required to perceive the real state of one’s marriage, though doubtless the latter is much more difficult.

Is Murdoch still thinking about Snow, with this remark? I think she is. For one thing, back when Snow was a scientist, he was in fact a chemist!

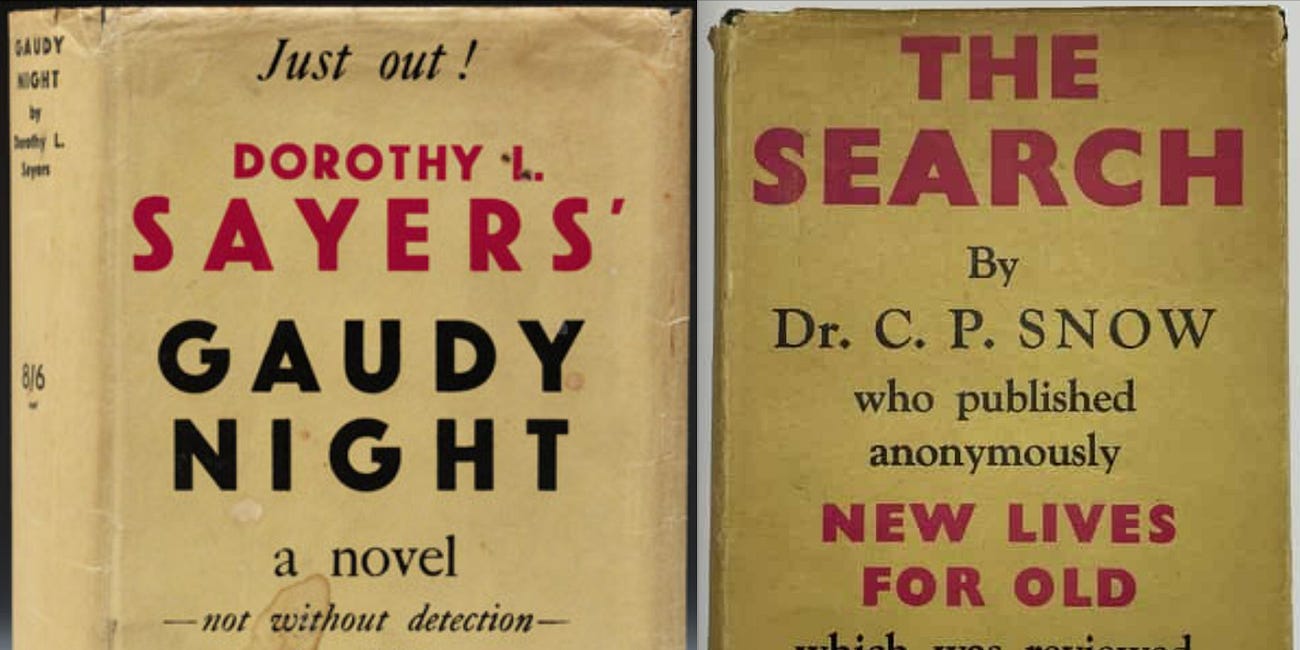

Thus far I am quite sure of my conclusions, but I cannot resist an additional stretch. In Snow’s novel The Search, published in 1934 after he gave up science to be a writer, a scientist falsifies a result for professional gain. Less than a year after The Search was published, Dorothy L. Sayers included Snow’s novel as a plot point in her own detective novel Gaudy Night. Sayers, in her usage of The Search, makes this same equivalence between honesty in chemistry and honesty in history. It is in Gaudy Night, in the context of history, that we are told of a crucial character who once failed to tear up his own theory when presented with a countervailing fact.

It is entirely plausible that Murdoch the philosopher-novelist would follow Snow into his—and others’—fiction writing in order to properly consider his argument that science has close links to our moral development. She resists Snow’s suggestion that scientific understanding might be necessary to fully comprehend this link, and I shall not attempt to adjudicate that point of contention. What is far more interesting to me is the way that Murdoch and Snow agree on the importance of seeking to see truly, as practised in science but not exclusively in science. If anything, Murdoch does a much better job of conveying this moral importance than Snow does!

In The Two Cultures and in The Moral Un-Neutrality of Science, Snow appears to be tapping into a philosophical intuition that he cannot fully articulate. Stephen Jay Gould, in The Hedgehog, The Fox and The Magister’s Pox, recalls that he followed the “two cultures” controversy with eagerness as an undergraduate. However, he continues, “[M]y rereading of it, as I prepared to write this book, left me with a feeling of disappointment and much ado about nothing.” Likewise, in A View from the Bridge: The Two Cultures Debate, Its Legacy, and the History of Science, historian of science D. Graham Burnett credits an encounter with The Two Cultures as a sixteen-year-old for influencing his choice of field, and yet notes that, when re-reading it as a graduate student, he found “a new distaste for the essay.”

When I was a young, ardent student of the physical sciences, I had this same experience of seeing something in The Two Cultures—and I, too, failed to find it, when I went back to the essay years later and tried to put my finger on it. Unlike Gould and Burnett, however, I am reluctant to conclude that the address was empty all along. There’s something there, almost, before Snow leaves the abstract theorizing behind and turns to public policy.

In The Sovereignty of Good, Murdoch fleshes out her indication about the importance and difficulty of trying to see truly by giving a virtue-ethical nod to the role a science or craft—a τέχνη, to use the Greek word that Murdoch borrows from Plato—can play in developing a person’s character. Her approach is echoed by Alasdair MacIntyre’s Aristotelian perspective in After Virtue, which gives a central role to practices which inculcate virtue and are directed towards a shared good.

Snow’s novel The Search depicts chemistry as a practice/τέχνη in this sense. The book refers, early on, to the narrator’s “first glimpse of scientific unselfishness,” when the staff of an institution where he does not even work take the time to diligently teach him about crystallographic methods. Scientists, in this story, share a goal of truth-seeking, and some will gladly share both expertise and equipment as a result. The scientific community of The Search also has its bad apples, of course. Still, science as a whole is portrayed as a community with a central moral vision from which co-operation naturally proceeds.

As a result, the moment when the narrator of The Search knows that he is no longer a scientist, can never go back to being a scientist, is the moment when he gives up on this moral vision. When he chooses not to expose his friend’s deliberate publication of a scientific falsehood, he is “breaking irrevocably from science.”

Science has provided us with new standards of rigour in truth-seeking, for example by reducing the weight that we place on tradition and popular wisdom, and by raising the salience of corroboration between different techniques, or different observers, in order to measure reliability. Those changes in the way we perceive truth have an impact on how we understand the virtue of honesty. To be honest—either with oneself or with others—is to faithfully seek and acknowledge ones own best judgment as to the truth: about science, or about history, or indeed about interpersonal relationships, as Murdoch notes.

It is rightly noted by many that science has limitations. Sometimes, indeed, the notion that science could justly affect our moral and spiritual lives is dismissed as “scientism” as soon as it has been raised. Stephen Jay Gould famously described religion and science as operating in “non-overlapping magisteria.” But Murdoch’s holistic Platonism does not allow for such a clean separation. Instead, we see that while science is reliant on a moral vision, it is necessarily also a contributor to that moral vision, because it is a practice within which we learn virtues that can apply in other contexts.

I am sincerely impressed by Iris Murdoch’s ability to take a claim to which she was initially hostile, look at it in depth, and provide it with a substantiation that takes it far beyond its initial expression. Snow himself, though he shares much of Murdoch’s cultural background and with it some classical tendencies, cannot ground the instincts he is gesturing at in a deeper worldview. Murdoch can.

Moreover, I do not think that this connection that Murdoch has noted between science and virtue ethics can be ignored by other virtue ethicists. The concealed depths in Murdoch’s way of including science stand in stark contrast to a notable shallowness on the same subject in Alasdair MacIntyre’s work.

After Virtue dances around science in a variety of ways. The seventh chapter freely acknowledges that “The modern contrast between the sphere of morality on the one hand and the sphere of human sciences on the other is quite alien to Aristotelianism because, as we have already seen, the modern fact-value distinction is also alien to it.” Despite this, MacIntyre laments that the Aristotelian account of human action should have fallen out of favour at the same time as the Aristotelian understanding of nature (by way of the scientific revolution) and theology (by way of many currents in the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation).

Given the holistic nature of Aristotelianism that MacIntyre already acknowledges, it is surely understandable that problems with this worldview in one area would be taken to pose problems in other areas. Of course, this does not prevent us from looking backward to earlier traditions when attempting to mend holes in our own, but it does suggest that some of the problems that Aristotelianism ran into may have been genuine, and in need of being addressed in some way.

This issue intensifies in MacIntyre’s follow up work, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? By this time, MacIntyre has converted to Thomas Aquinas’ account of virtue ethics, and, with it, to Catholicism. As we have noted, MacIntyre’s worldview is holistic. There is no fact-value distinction; there are no non-overlapping magisteria. Yet MacIntyre’s historical narrative jumps straight from Aquinas, in the thirteenth century, to the Scottish Enlightenment, in the eighteenth1 century, rendering the scientific revolution suspiciously silent.

Whose Justice? makes much of the virtue of honesty, conspicuously noting which worldviews have an absolute prohibition against lying and which do not. Yet the book’s attitude to truth is far more ambiguous, declaring airily that “facts, like telescopes and wigs for gentlemen, were a seventeenth-century invention.” Does MacIntyre therefore propose to dispense with the concept of a fact? It would appear so. He substitutes, instead, an idea of “truth” as formulated within an intellectual tradition.

I suspect sophistry. Science is an intellectual tradition, albeit one that we have been struggling for centuries to fit into a broader and more holistic understanding. MacIntyre may flirt with the idea that it was a false step, but I remain convinced of its truth-seeking utility.

Moreover, when it comes to the virtue of honesty, I place far greater importance on the integrity required to be honest with oneself than I do on whether it is acceptable to lie to Aunt Agatha about the aesthetic qualities of her ugly hat. To be sure, I dislike lies and have found that the attempt to be truthful even in minor matters can have unexpected benefits. But to be persnickety about honesty in small social matters even as one slurs over the truth in ones wider understanding is a real “straining the gnats while swallowing a camel” kind of move.

It can be an advantage or a disadvantage to make links between ethics and science. There is something very powerful in the way that Iris Murdoch incorporates a Platonic love of truth into her worldview, and integrates it with scientific truth-seeking even as she insists that science is but one part of our search for the true and the good. By contrast, when MacIntyre advocates for pre-Enlightenment holism, it is a real weakness when he tries to gloss over the subject of how we ought to see science in this context.

Snow and Murdoch together have furnished us with an insight that virtue ethicists ought not to ignore. Truth is important to morality, and the practice of science can give a moral education that affects how we see truth. Any historical story about why religion and ethics have developed in the way that they have will be incomplete if it does not take this influence into account. Philosophies that draw on the classical tradition can become less convincing if they do not adequately address science; on the other hand, they can also become more convincing when they handle science well.

By the way, I have written before on The Search and Gaudy Night, here:

Snow, Sayers and The Search

This post contains spoilers for Gaudy Night, The Search, and Middlemarch.

Many thanks to John Encaustum for pointing out that this isn’t quite accurate. In fact, there is a little bit about the seventeenth century, as prelude to the Scottish Enlightenment. However, this jump still takes the scientific revolution as a fait accompli. My main point stands, though I regret the error and appreciate having it pointed out.

I think this is pointing to exactly the right questions, re MacIntyre's history of rationality. I'll write a note-restack expanding on that agreement later, but in the meantime: well-chosen objections!

Excellent post.

It is odd to me that more virtue ethicists don't more commonly draw on biology. It seems to me to fairly straightforwardly vindicate the basic Aristotelian picture of humans as being made to be rational social animals, and ethics being largely a result of that nature. And if we look at how for other animals we try to let them exercise their particular natural capacities in order to guarantee their flourishing (eg keeping social animals in groups, giving dolphins space and opportunity to play and use their brains), this fits exactly with Aristotle's idea that our happiness relies on us exercising our distinctive human capacities.