Time and Metaphysics

Galileo and Kant and Mach and Einstein

This post, I must warn you, is one long digression based on what was at the time a somewhat under-researched side remark in a comment I made on a Wisdom of Crowds episode. Properly giving substance to what I was getting at would probably have taken a good-sized post even if I had done so as efficiently as possible. Moreover, the subject matter was always going to be a little bit mind-bending, even before I decided to bring Kant into it. I was already fizzing with additional thoughts when I posted the original comment, so when Samuel Kimbriel said he’d like to know more I am afraid I just sort of went “Oh, you want me to go on a tangent?” and then floored it.

I have not hesitated to make side remarks upon whatever catches my fancy, be that the ethics of expertise, the social effects of precise time, or the Problem of Evil. I have, however, managed to confine the bit about real analysis to a lengthy footnote that can be skipped.

It was the holidays, okay? I promise I’ll recover my self-control in future.

I. Pendulum

Galileo Galilei created the first known design for a pendulum clock in around 1637, a few years before he died. It was never built, but the underlying principle was that the period of a pendulum does not depend on its amplitude. So even though, over time, the extent of the pendulum’s sway will decay, the time it takes to go from one side to the other will remain the same. Galileo is said to have first noticed this fact about pendulums in the cathedral at Pisa. The story goes that he was attending mass when he looked up, observed a swaying lamp, and timed it with his pulse.

Like many Galileo stories, this one is disputed. Vincenzio Viviani knew Galileo personally, and his account of Galileo’s life is certainly based on fact. But there are places where we know he was, uh, creative with detail, and that calls some of his other claims into question. “At that time,” explains historian of science Michael Segre, “history could still be written as a moral lesson, as a forum for philosophical or religious ideas, or even as part of a literary enterprise.” Still, Segre makes a documented case that Viviani, who was himself both perfectionist and empiricist, did care about getting things right.

In an earlier post on science and virtue ethics, I claimed that greater precision in how we relate history is influenced by the development of scientific ideas about truth. But the relationship is not a straightforward one, because there is a step in the middle that involves developing practices for finding and understanding historical facts. The subject of history requires its own specialised virtues. The practices used by modern historians in seeking truth are not always followed even by modern scientists, when relating history. Viviani was a Renaissance scientist, and we should not be surprised that he wrote history as it was written in the Renaissance.

In this case, the timeline given by Viviani for Galileo’s initial realisation about the pendulum doesn’t match what we know about when the existing lamp was put in. On the other hand, Galileo himself emphasises the use of a human pulse to measure time, so that part of the story is entirely plausible. It could have been a different lamp; it could have happened later than Viviani said; it could be a story told to keep the interest of the audience. But wherever Galileo got the idea, Galileo’s own writings explain that he went on to experiment with lengthy pendulum observations, timed not by pulse but by water clock, and comparing the period of a heavy lead pendulum with a lighter cork one1.

Galileo made two claims: that the pendulum’s period does not depend on the amplitude, and that the pendulum’s period does not depend on the pendulum’s mass. Both claims have issues, yet each of these claims is powerful. The lack of dependence on amplitude is actually only nearly true, and only when the oscillations are small (as they would have been for most of a long experiment, because the larger swings would have died down quite quickly). Once people had that figured out, though, it became possible to make extremely accurate clocks by using an escapement that would automatically limit the size of the swing. Pendulum clocks were the most precise timekeepers in the world from the mid-seventeenth century right up through the first few decades of the twentieth.

As for the lack of dependence on mass, it’s complicated by the effect of air resistance. When released from a wide angle, a cork pendulum will initially swing with a smaller period than a lead one because it will reach the smaller amplitudes more quickly. Without the effect of air resistance, however, this claim really does check out, whether the swing of the pendulum is wide or narrow. It’s a sub-category of the fact that the motion of an object under gravity is in general not dependent on the object’s mass. On the Earth’s surface, minus the effect of air resistance, absolutely everything accelerates downward at about 9.8 metres per second squared, whether it is heavy or light.

Galileo had an eye for invariances. As a natural philosopher he was a staunch advocate of mathematics and of measurement; he was looking for a geometry of motion. In addition to the above-mentioned invariance in what we would now call gravitational motion, he also gave a description of invariance under inertia. He used a ship as an example, but these days it is more common to reference a train. Specifically, if you’re on a train next to another train, sometimes it can be hard to tell whether your train is moving or the other one is. You can see the other train move, and mistakenly think that it’s because you’re moving, or vice versa. The laws of physics in a train carriage moving in a straight line at a constant speed are the same as those in a train carriage at rest. Unless you’re accelerating, it can be hard to tell if you’re moving or not.

Einstein referred to this as the “principle of relativity” because one way of responding to this is to make the ontological claim that there’s no such thing as being absolutely at rest. Instead, inertial (i.e. non-accelerating) motion is only ever “moving” or “stopped” relative to some designated (non-accelerating) object that we define as “at rest.” This principle, from which Einstein’s theories of relativity get their name, was not invented by Einstein. It was developed from Galileo’s observation, long before Einstein entered the scene.

You might be thinking, in that case, what did Einstein do? The answer is that Einstein found a way of reconciling this principle with our understanding of electromagnetism. You see, Maxwell’s electromagnetic laws prescribe the speed of electromagnetic waves (such as light) in a vacuum. That’s potentially a problem, because the principle of relativity forces us to ask, speed relative to what? If light is a wave, then it should probably be speed relative to the medium in which the wave propagates, but if the light is in a vacuum then what’s it propagating in? For a while, people thought the answer was some sort of universally present “luminiferous ether.” But in that case, if we’re smart, we should be able to measure our own motion relative to the luminiferous ether by observing the behaviour of light relative to the Earth’s motion. Maybe we could even define the motion (or otherwise) of objects relative to this ether, wherever it is.

Problem is, they couldn’t find it. Best anyone could tell, with cleverly-calibrated and extremely sensitive experiments, light seems to be travelling at the same speed no matter who does the measurement or how the measurement equipment is moving.

II. Inconvenience

Story time. When I was at Cambridge, a fellow student asked me for book recommendations on physics. He was a postmodernist, and he wanted to know about relativity and quantum mechanics as seen by physicists. I’d spent most of my teens reading popular books on the subject and could compare with the more mathematical knowledge I’d gained on those subjects in undergrad, so it was easy enough to send him to the book I thought clearest and best.

He came back to me a few days later with a question. He’d read the first couple of chapters and he reckoned the relativity stuff mostly made sense. I mean, time being different for different observers, that checks out, he said. Variations in measured spatial differences, likewise. But he had a problem with the speed of light being the same for all observers. “Isn’t that just a bit—convenient?” he asked.

Yeah, he really said that.

Now, I was in the middle of eating breakfast at the time, and I’m afraid I wasn’t very thorough with my response. I believe I simply gave him look and said “Um, no.” I could have tried to give him a lengthy explanation as to why this fact is really not convenient at all, but it would have taken a while, and, you know, breakfast.

It really isn’t convenient, though.

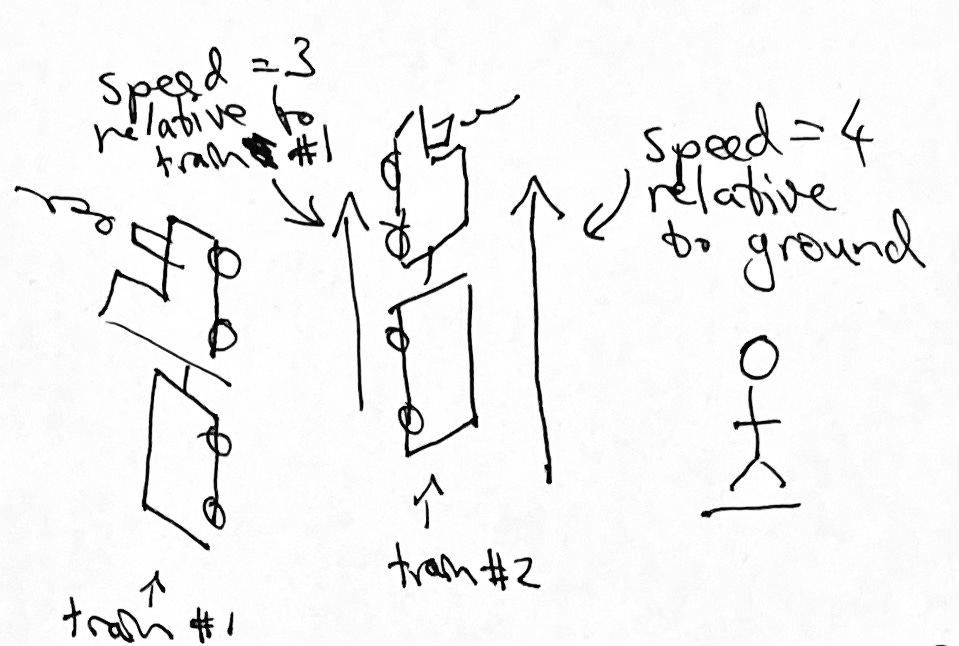

Look at it like this. If I’m on train #1, going north, and I see train #2 going north at what to me looks like a speed of 3 units, and you’re on the ground and you see the same train #2 going north at 4 units, then my speed must be your measurement minus my measurement, right? So my speed is 1.

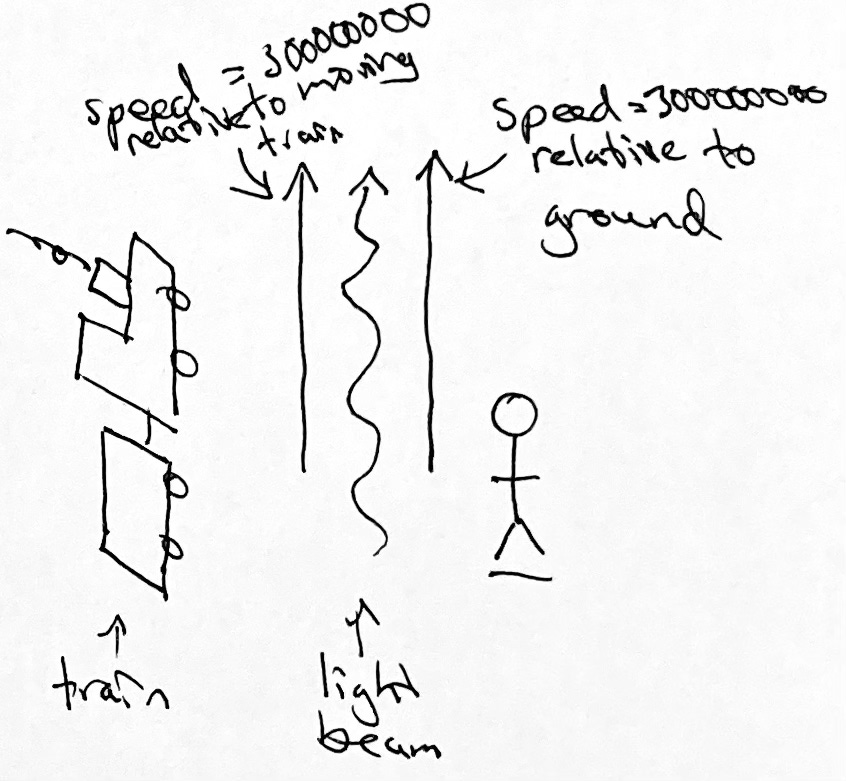

So let’s do that with light. I’m on a train, going north at speed 1, and you’re on the ground shining a beam of light northward. I measure the speed of the light, which turns out to be2 300,000,000. You measure the speed of the light, and you also get 300,000,000 because the speed of light is the same for all observers3. So my speed must be your measurement minus my measurement, like before with that train that was going at speed 3 relative to me. So my speed is 0. So 0 equals 1.

Folks, this is not convenient. This is very, very bad.

Now, playing devil’s advocate, you might want to argue with me that this is still convenient, because luminiferous ether, if it existed, would potentially contradict the ontological—dare I say, metaphysical—claim that there’s no such thing as being absolutely at rest. I won’t deny that there are reasons someone might prefer that ontological view; Einstein did. It’s more symmetrical, in the way that physicists use the term. Just as mirror symmetry4 means that something looks the same in a mirror, and rotational symmetry means that something looks the same when you turn it some specified angle, what we have here is a kind of symmetry in the laws of physics between motions at a constant speed.

So, sure, the situation with everyone seeing light moving at the same speed might be more beautiful, except that “0 equals 1” is ugly no matter how you look at it. We can fix this problem, but, in the process, a lot of apparently obvious things will have to change.

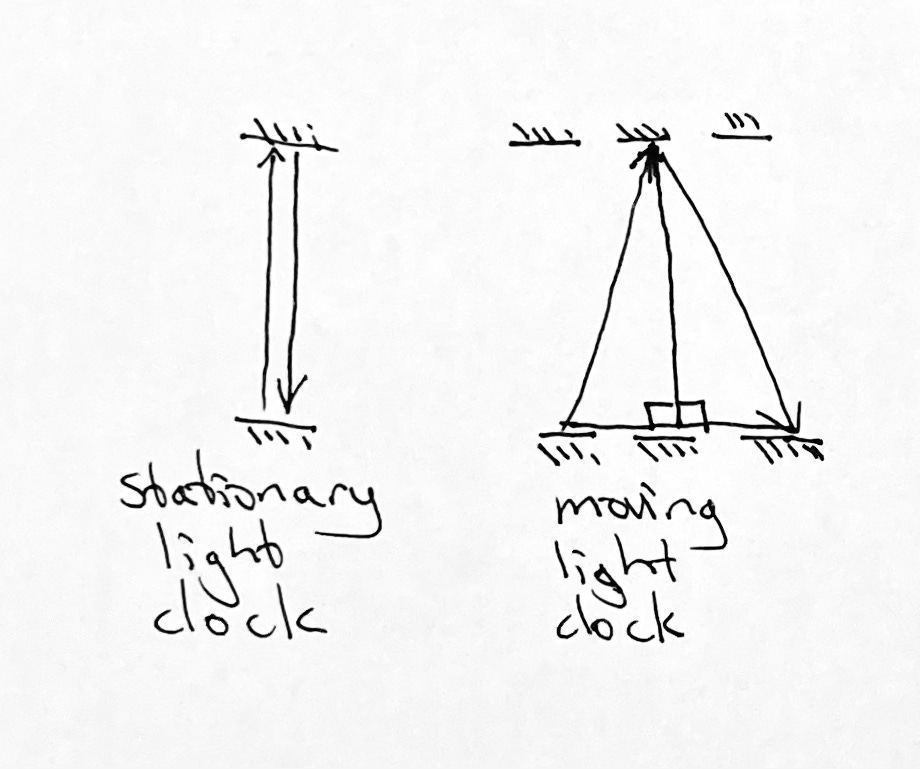

Here’s a relevant theoretical consideration. What would happen if, instead of using a pendulum, we used a reflected beam of light to measure time? Let’s make the light beam move vertically between mirrors that are a distance of 1.5 units apart. In the slightly-abstract units that I’ve set up, that means the light travels the 3 units up and back in 0.000000001 units of time.

But what if this “light clock” is moving? That would mean that the light is travelling a bit further, right? It has to travel the hypotenuses of the pair of triangles on the right:

If the “light clock” is moving at a low speed, then these triangles are going to be pretty narrow, so the hypotenuse won’t be that much longer, but it will be a little bit longer. The light is still travelling at the same speed—it has to—so the clock will be just a teensy bit slower to measure its 0.000000001 units of time. This is one of the simplest ways to see one of the most well-known facts about relativistic physics. Moving clocks run slow, whether they are “light clocks” or not5.

Even more confusingly, this “relativity” in the passage of time is itself relative. From the ground, it looks like time on a moving train runs a little bit slower. From the train, however, it looks as though time on the ground is running a little bit slower. (Symmetry!) You should expect this apparent6 paradox, because the entire point of this whole exercise was to keep that principle about relativity of motion that was already perceptible to Galileo.

Keeping track of these kinds of changes in time and space is the key to solving the addition-of-speeds problem so that it no longer gives us that horrible “0 equals 1” effect that we saw above. I’ll spare you the math. What I want you to notice is that the invariance of the speed of light for all observers is directly related to this very precise but deeply weird distortion in the passage of time depending on the speed of the clock that does the measurement. The relativity of time and the invariance of light speed aren’t opposites. The rigidity of the latter is part of what forces the flexibility of the former.

Anyway, this is the explanation that I didn’t give to that postmodernist. I took another mouthful of eggs, instead.

Not long afterwards, I learned that he had found himself seated near a physics professor at a formal dinner. Emboldened by the copious amounts of available alcohol, he attempted to make his point about the “convenience” of the speed of light in a vacuum being the same for all observers. I would dearly love to have seen the conversation. Alas, I had to be satisfied with watching our mutual friends rag him about it afterwards!

To his credit, he gamely submitted to the general merriment at his expense. His one moment of protest was when he ventured in his own defense that that if we had been seated next to a critical theorist and had tried to have a conversation about Derrida then we wouldn’t have been very successful, either. This is probably true, although at the time I remember thinking that it was also rather unlikely that we would have tried! Then again, in this piece I myself am certainly ranging quite freely outward from my own areas of formal education, so I suppose I had better be a little cautious.

I do think that there is something very dark about the notion that obscurity of one’s subject ought to be seen as status-inducing. I know it plays out that way for physics, sometimes, but I think it matters that this is not the point. Ideas, when they are difficult, should be difficult for some reason beyond the allure of obscurity. In the case of relativity, there is an immediate purpose here—namely, the rectification of an inconsistency between electromagnetics and mechanics—that feeds into a broader purpose of attempting to accurately describe the physical world.

Of course, we must therefore ask if relativistic mechanics does accurately describe the physical world. It took a surprisingly long time to test it directly; the committee for the Nobel Prize in Physics actually got tired of waiting and instead gave the award to Einstein for a different 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect that was a crucial step on the way to quantum mechanics. Einstein himself suggested testing the relativistic Doppler effect of light, but it took until 1938 to successfully implement that experiment.

It gets harder to accelerate things the closer they get to the speed of light, and this effect is stronger for more massive objects, so it’s quite hard to get a strong relativistic time dilation effect on a large object. On the other hand, small particles are regularly accelerated to an appreciable fraction of light speed in particle colliders, and relativistic effects in how long it takes them to decay have been thoroughly observed. But if you want the kind of direct experimental verification of the time dilation effect that you might most easily imagine—in which one clock moves, and another one remains stationary, and then we compare them—well, that took even longer to become possible. We needed to build a better clock. The first experiment of this nature was the Hafele-Keating experiment in 1971, and it used a caesium-133 atomic clock, operating on a principle that was prototyped in 1955.

Time has changed; or, at least, our measurement of it certainly has. Prior to the development of pendulum clocks, it was normal for a timekeeping device to lose about 15 minutes a day. True time was kept by the sun, and everything else was a rough estimate. By contrast, even quite early pendulum clocks would lose no more than 15 seconds per day. Time could be measured more precisely, and that meant we could be held to it more precisely, too.

Einstein’s discovery of a relativity in how different observers measure time led to speculation that these strictures might be loosened. Perhaps we might no longer expect everyone to be precisely tethered to the same time measurements? It hasn’t played out that way, though. Relativistic time dilation is a vanishingly small effect in most situations. For specific applications where it makes a difference, we just take it into account and keep on measuring, as precisely as we can.

We don’t even define our units of time by the sun any more. The official definition of a second is the time taken for 9192631770 vibrations of a light wave7 coming from the unperturbed ground-state hyperfine transition of a caesium-133 atom. We do sometimes add leap seconds so we can stay in phase with the sun, however.

You are probably reading this on a device that is regularly updating the time it tells you, based on International Atomic Time. You probably carry such a device around with you most of the time. You are tethered in a quotidian fashion to the time measured by a few hundred atomic clocks in laboratories around the world. Relative time? You wish. We are all, almost always, absurdly in synch.

III. Heartbeats

I have to admit, the considerations in my last couple of paragraphs made me feel a bit queasy, when I first thought of them. Don’t get me wrong, I am glad that atomic clocks exist. I consider it a remarkable human achievement that we can measure time so precisely that we are able to perceive the tiny relativistic variations in it, and of course it is only natural that we would use the same technology to keep track of our own local time, as a species. But is it good that we live our lives constantly checking it? Have we made ourselves slaves to a bunch of caesium atoms?

So—it being the summer holidays, after all—I left my phone on the floor when I woke up the next day, in the bunk room of a large house up in the mountains where we and the relatives were staying for a couple of nights. My husband and kid were keen to go to the pools and so was I, so we walked over there as soon as we felt like it without bothering to check the time. And when I had a moment, I left my husband to accompany my kid down the hydroslides, and wandered over to sit in the geothermally heated water that gives the original raison d’être to the water park.

I sat in the water, and timed things with my pulse. It took 92 heartbeats for all the bubbles to pop after I swirled the water. It took 43 heartbeats for a cute little kid to navigate the long ramp out of the water. A sparrow hopped on a nearby rock for 11 heartbeats.

Most natural processes are pretty irregular. It cannot have been simple to find timings that would repeat in a predictable fashion.

Easier to find one when you know what to try, of course. I tapped the surface from below with a finger and timed the resulting circular wavefront. Two heartbeats to be over the vent at the bottom. Not very accurate, but it didn’t need to be. I dragged my finger across the same distance, faster than two heartbeats. There it was, a triangular wave: gentler than, but still analogous to, the Mach wave caused by objects that travel faster than the speed of sound.

Ernst Mach is best known, these days, for his work on supersonic fluid mechanics, including the calculation of the wave produced by the movement of a supersonic object. The resulting crack is known as a sonic boom. In the water where I was sitting, the triangular surface wave behind my finger made a much more familiar sight, like the bow wave of many a ship.

Mach was a polymath, though. He had interests in physiology and psychology, and his philosophy of science had a profound influence on Albert Einstein—sometimes as inspiration, and sometimes as foil.

Mach credited his philosophical awakening to reading Kant’s Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics at age fifteen. Kant distinguishes very carefully between things in themselves, and things as we perceive them, and stresses that we only have access to the latter. Mach, seeing no use for the former if we can’t even perceive it, developed what was termed in his time a ‘phenomenological physics,’ in which theory is essentially a summary of experiment, a way of efficiently condensing the empirical facts that we experience.

Mach wanted to remove metaphysics from science altogether. But what did Mach mean by “metaphysics”? Presumably, he meant whatever Kant meant by it.

Well, if Mach could handle Kant’s Prolegomena at fifteen, I reckoned I could probably handle it at forty, so I downloaded Paul Carus’ translation8 from Project Gutenberg and read it from start to finish.

IV. Geometry

Famously and influentially, Kant’s main definition of metaphysics is that it consists of a priori statements that are synthetic rather than analytical. Analytical statements, per Kant, are those that explain what we already meant by our terms, or logically expand on a definition. Synthetic statements have actual content. A priori knowledge is knowledge prior to experience. So “synthetic a priori” knowledge is substantial but not empirical. It’s a conceptually pleasing definition. Obviously, it’s also controversial.

The interesting thing about reading Kant’s Prolegomena with my background is that Kant makes extensive use of mathematics and physics in order to demonstrate his desired approach on subjects less controversial than God or the soul or the nature of physical substance. It’s wonderful: sharp, elegant, thought-provoking, and, from the point of view of the 21st century, also a bit of a hot mess. I love it.

Space and time, says Kant, are part of that synthetic a priori. They are not experienced; rather, they are part of how we interpret our experience. We need them to make sense of our sensations; thus, they must be prior to empirical perception.

Kant makes the fascinating and fateful argument that this inherent perceptual aspect of space and time makes these things more certain, not less. Precisely because we are unable to perceive objects in any other way, we can be sure that this aspect of our understanding will not change. Thus, it does not make sense to ask “Does [Euclidean] geometry correspond to the real world?” Geometry is part of—and necessary to—our perception of the world, and is in that way safe from refutation.

So when Ernst Mach tries to excise metaphysics from physics, one of the things he takes aim at is this notion of space and time. He draws heavily on that Galilean notion about the invariance of the laws of physics under constant motion. Movement, he stresses, is movement relative to some other designated thing. We can measure distance without making claims about space; our measurements are perceptions. Should we even have this metaphysical notion of “space” that Kant insists we cannot do without?

Einstein’s first 1905 presentation of his theory of relativity draws on Mach’s approach. We can loosen our notions of space and time by fixing them to specific measurements, instead of treating them globally. The resulting flexibility can then be used to accommodate this difficult fact about the invariance of the speed of light, relative to observers.

However, note that this new, altered way of reckoning with space and time was then re-globalized, by Einstein’s former teacher Hermann Minkowski. We don’t want any more of that kind of “0 equals 1” problem that I outlined above, so we want there to actually be a global system in which all of these changes are consistent with each other; Minkowski showed that there is one. Space and time are folded together into a new notion of spacetime. Just as we can change our spatial co-ordinates by moving the zero point, or rotating our angle of view, we can change our spacetime co-ordinates depending on how fast we are moving, and in what direction. It’s still deeply weird, but at least we have that globally consistent perspective to fall back on; we’re not just floating in a sea of measurements and hoping it all works out. So we haven’t necessarily moved to a purely measurement-based approach. This level of theory is still consistent with Mach’s philosophy, but it doesn’t force us to adopt it.

On the other hand, even if we don’t have to adopt Mach’s worldview, things are looking kind of bad for Kant. Time and space do not seem to be certain and unchangeable in the way that “synthetic a priori” knowledge ought to be—and the situation is about to get worse.

Minkowski spacetime could make sense of relativistic mechanics, but it left one aspect of Newton’s old physics wide open for reinvention. In relativistic mechanics, anything that requires instantaneous changes across large distances no longer makes sense, because the very idea of something being instantaneous is now relative to our chosen co-ordinates; we don’t have a universal global time. But Newtonian gravity is instantaneous, as originally formulated. A mass moves, and its gravitational field moves with it, all at exactly the same time, across the entirety of space.

Einstein spent several years formulating his own theory of gravity that could fix this issue. The version he eventually found draws on yet another symmetry observation from Galileo. Remember, above, I mentioned that the motion of a pendulum doesn’t depend on its mass, and that this is a special case of a broader fact about gravity: things would all fall at the same speed, if it wasn’t for the effects of air resistance.

This is genuinely peculiar. A more massive object with the same electric charge on it will move more slowly than a less massive object would, when influenced by the same electric field. But with gravity, this can’t happen. The gravitational equivalent of the electric charge, in this analogy, is the object’s mass. Massive objects are harder to pull, but gravity pulls harder on massive objects! The two effects always cancel out exactly.

Einstein put this observation together with another symmetry observation of his own: acceleration and gravity are remarkably similar in their effects. You might notice this, if you’re in a lift that is accelerating particularly fast up or down. If the floor is accelerating upward, you will feel as if you are being pushed downward into the floor by a stronger gravitational force. If the floor accelerates downward, it can make you feel momentarily near-weightless; your stomach might lurch in response.

To be in free-fall is locally indistinguishable from experiencing no gravity at all. The acceleration due to gravity precisely cancels out the acceleration-like effects that gravity would otherwise have. This, in fact, is the true reason why astronauts in orbit around the Earth seem to be floating in zero gravity. It’s not that they have escaped the Earth’s gravitational field; on the contrary, that field is the thing keeping them in orbit! But the way an orbit works is by travelling fast enough to move past the Earth in the time it would have taken to fall down into it. An orbit is a kind of free-fall, falling around instead of down.

Free-fall is locally indistinguishable from being motionless—or travelling in a straight line—in the absence of a gravitational field. So Einstein’s theory of gravitation proposes that free-fall actually is motion in the local version of a straight line. It’s just that the “straight line” is on a surface that is curved. The presence of a massive object causes a curvature in spacetime that affects the way things move. We see these changes in motion, and call them gravity.

From here, we can give an explanation for why objects of different mass are affected by gravity in the exact same way. They are travelling in “straight lines” over the same curvature in spacetime. The invariance that Galileo saw, all those years ago, finally has a reason behind it.

V. Motion

It’s worth pausing, here, to admire the longevity and flexibility of Galileo’s style of describing physical motion. Newton is justly admired for forming a precise mathematical system that could describe celestial and terrestrial mechanics in a unified whole. But when it came time to re-think that system, it was Galileo’s symmetry observations that formed the backbone around which the new system could be arranged.

In an earlier post, I criticized Iris Murdoch for suggesting that Aristotle might be considered the “Shakespeare of science.” Mary Jane Eyre suggested in response that perhaps the idea of a “Shakespeare” in science does not quite make sense; that science is less about individual thinkers and more about the knowledge created by many, over time. This is a very sensible way of looking at it. Also—hear me out—the Shakespeare of science is Galileo.

Galileo is a thinker on the cusp of modernity, making elegant, perceptive observations of the world around him in ways that can fit into many different future systems. His work is picked up by later thinkers in ways that leave the original inspiration visible even as they allow for further creativity. Galileo also represents something important about how scientists think of themselves. His anti-Aristotelianism, which is aimed chiefly at those who follow Aristotle too rigidly rather than at Aristotle himself, is the original example of a specific style of rejecting tradition that scientists continue to revere.

Francis Bacon is often referenced, when thinkers in the humanities try to characterise the ethos of science. Galileo, somehow, is not. But scientists almost never talk about Francis Bacon (whose actual scientific work was much less prominent). We do talk about Galileo. Most of us don’t read Galileo, but he is quite readable. You could put The Assayer or Two New Sciences or that all-important Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems into a humanities-style reading course and he’d fit right in. Galileo should be one of the people you think of, if you’re wondering why we don’t all follow Aristotle any more. We should care about the details of how that change happened, instead of just shrugging and making a quick remark about “science” as if it were unnecessary for any non-specialist to examine the subject further.

Aristotle’s claim that moving objects naturally return to a state of rest—an absolute state of rest—is central to his understanding of the cosmos and indeed to some very important aspects of Aristotle’s metaphysics. You see, Aristotle also observes that, notwithstanding this (supposed) tendency for objects to cease moving when not pushed, the stars and planets nevertheless continue to move, steadily, day after day. He concludes that they each aspire to imitate the perfection of an immaterial, unchanging, “unmoved mover,” and that they therefore move in circles because a circle is the most perfect of shapes. In turn, those stars and planets then influence life here on Earth.

For Christians influenced by Aristotle, it seemed natural to equate the outermost unmoved mover—Aristotle’s “first cause” or “prime mover”—with God. But the concept of inertia changes all of that. The planets no longer need anything to inspire them to keep moving. They keep going unless something stops them. God ceases to be seen as constantly giving new motion to a universe that would otherwise always be slowing down. Instead, we get the Enlightenment clock-maker God, who created a world that could manage itself.

Among other things, I think this change sort of heightens the Problem of Evil. Instead of a God who breathes new goodness and motion constantly into a world that naturally resists this force, we have a God who is responsible for having calculated every last detail. Asking God to reverse an evil is no longer asking God to make God’s presence felt where God seemed to be absent. Instead, it becomes more like asking a God whose will is everywhere to change that will. It’s a totally different perspective.

For those who might hope that modern physics provides an opportunity to repudiate the Enlightenment and return to something more Aristotelian, I can offer no encouragement. Recall that this change in how we conceive of God is a consequence of the notion of inertia—on the idea that motion in a straight line, and the state of being at rest, are equally inclined to continue indefinitely. This equivalence between straight line motion and being at rest is the “principle of relativity” in Einstein’s first relativity paper. It’s still here. It’s still central.

VI. Reality

We call that first 1905 theory “special relativity” because it is a special case of Einstein’s theory of gravity—which we now call “general relativity.” So here’s an important question. Is general relativity a physical theory, or a metaphysical theory? Or could it be both?

As a physical theory, it certainly makes measurable predictions. These include a correction to the predicted orbit of Mercury (thereby solving an existing mystery as to why Newton’s theory wasn’t quite getting Mercury right), precise predictions for how gravitational forces ought to affect light (famously measured by Arthur Eddington), small distortions in time due merely to remaining stationary with respect to existing gravity (relevant to making precise GPS measurements) and plenty more.

On the other hand, general relativity makes substantial claims about the very nature of space. Spacetime, in general relativity, ceases to be an empty background and becomes something that can change over time. In fact, spacetime can be changing, all by itself, even if there are no objects in it! Einstein’s theory allows for the possibility of gravitational waves, transmitting energy across long distances via a moving distortion in spacetime. The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for detecting them experimentally.

Kant’s Euclidean space couldn’t do anything like this: it was incapable of any kind of curvature, and it was an internally-constructed background for our perceptions of material objects; it couldn’t possibly do things on its own! So, just as inertia had metaphysical implications because of what it said about Aristotle’s wider system, general relativity has metaphysical implications because of what it says about Kant’s wider system. Kant claims that his deductions are reliable. He goes so far as to say that his theory stands or falls as a whole; he clearly means it when he says that there could never be a refutation of even the smallest part of it.

Yet, refutations we have. Lots of them, all over the place. Honestly, reading the Prolegomena, I started to feel a bit sorry for him. Kant remarks that we cannot expect to know why rigid objects can’t occupy the same space. I read that, thinking, it’s because of the Pauli exclusion principle. Kant says that we can’t know if the universe had a beginning. I read that, thinking, yeah, it’s technically true that we don’t know that, but the cosmic microwave background sure is suggestive.

Kant thinks he knows where the physics ends and the metaphysics begins. In fairness, Newtonian physics was taken by a lot of people to be basically certain. You can find plenty of philosophers wondering how to account for its certainty, prior to the point where we learned that we shouldn’t have been certain at all! Kant is not alone in his overconfidence.

I actually want to give Kant some credit. Look at this, in §40:

Pure mathematics and pure science of nature had no occasion for such a deduction, as we have made of both, for their own safety and certainty. For the former rests upon its own evidence; and the latter (though sprung from pure sources of the understanding) upon experience and its thorough confirmation. Physics cannot altogether refuse and dispense with the testimony of the latter; because with all its certainty, it can never, as philosophy, rival mathematics. Both sciences therefore stood in need of this inquiry, not for themselves, but for the sake of another science, metaphysics.

All this deduction about mathematics and physics is proving the obvious, says Kant. There’s no reason to care about it, except as an exercise prior to the actually controversial metaphysics. He’s wrong, though, about there being no reason to care. The applicability of geometry isn’t trivial at all, and Kant’s capacity to see that there is substance here is, in itself, worthy of admiration. Kant is a fish who has taught himself to see water.

If Kant had not articulated this, would Mach even have been able to see and reject it? Would we have had the philosophical grounding that we needed, in order to take our understanding of space and time apart—and then put them back together in a new shape?

“Synthetic a priori” is not Kant’s only definition of metaphysics. Later in the Prolegomena, he gives a lovely mathematical analogy. Physics, he says, is like the interior of a shape. Some metaphysical ideas are kind of like its boundary9: not part of the shape, but suggested by it.

The thing about asserting that metaphysics can be completely reliable, and then locating metaphysics on the boundary of your physics, is that this means you are assuming that the physics is going to stay put, yeah? Oh, sure, some of the interior stuff might change, but the basic shape had better be permanently fixed.

Only it’s not.

Kant is right that there is a human process of perception that naturally locates things in an internal notion of space and time. However, the theory of general relativity suggests that there is also something about space and time that is not just about our perception, and that indeed is not obliged to conform to the shape that our perception naturally gives it! There is something about space and time that is real. That’s why they have the power to surprise us—to be, dare I say it, inconvenient.

Part of what we mean by saying that something is real is that it has limitations, that we can’t just make it into whatever we want it to be. This is important for understanding physics as a practice.

I would not try to claim with certainty that general relativity is absolutely true. Perhaps it, too will undergo some future, fascinating, metaphysical reinvention that will change how we understand space and time, all over again. One of the remarkable things about general relativity is that in most cases it gives results that are almost the same as Newtonian gravity, even though it operates on a totally different metaphysical basis10. Surely, then, we are forced to conclude that there might be other possible theories that would give equally good results, could we but find and describe them. Einstein would say that, in that case, we ought to make sure to pick the beautiful ones.

Yet even if there is an element of human creativity in our physical theories, that creativity is operating within stringent limits. We cannot just do whatever we like, not if we want to conform to experimental evidence. It is the very difficulties that physics can give us, in attempting to make sense of it all, that indicate that limiting reality, however hard it may be to truly discern.

Moreover, even a partial truth on an unknown metaphysics can be powerful and brilliant. Think, again, about Galileo’s observation of the invariance of the period of a pendulum with respect to its amplitude. The pendulum—based on our current best understanding—is moving due to the curvature of spacetime, but Galileo knew nothing of that. Subsequent horological work swiftly showed that the invariance in question is only approximate even at the best of times. There’s nothing fundamental about it. Also, we built our clocks around it for hundreds of years and they worked.

I still think Kant is right that science and mathematics are the things that border on the easy metaphysics, comparatively speaking, even when that metaphysics turns out to be very hard indeed. Society and politics and human purpose are harder. There might not be any absolute truths involved; it’s hard to be sure. And yet I think it is still right to wonder about the geometry of those harder subjects, the invariances that their relativities might bend around, whether they are absolute truth or merely a local symmetry. I can’t stop looking, even when there are some things I can only measure with the unreliable beat of my own heart.

As I write this, it is past 11pm on the 6th of January. That means it is still, barely, the feast of the Epiphany, when the wise men who studied the stars followed their observations and, we are told, arrived into the presence of a newborn baby that was and is the answer to everything.

I do not have the answer to everything. My perfect timing will be gone by the time I can edit this and double-check my facts. The stars are no longer held by those who study them most deeply to be portents of human affairs. The calendar is political and Eastern Christians say that it won’t be Epiphany for a while yet. Quakers believe that all time is sacred, not just feast days. Enlightenment thinking holds that time is even and empty. Einstein tells us that time is part of spacetime, and it does indeed bend around the sun, but not in any of the ways we previously thought.

I love it all. Thanks for reading. Happy New Year.

The speed of light in a vacuum is actually 299,792,458 metres per second, so I’m being a little bit abstract with my units to make the numbers nice and round.

Technically the light is travelling through air, making it a little slower than in a vacuum and not quite invariant, but the effect of air on the speed of light is very small.

Funnily enough, by our current understanding the laws of physics do not have mirror symmetry. Specifically, the weak nuclear force does not have mirror symmetry. One of C. P. Snow’s complaints in The Two Cultures is that this fact has just been discovered and yet “intellectual” culture hasn’t even noticed. Given the borderline-metaphysical importance of symmetries in physics, Snow has a point.

Yes, there is potentially another way to resolve this issue. Speed depends on both length and time. Why are we messing with the time and not the length? Either would be weird, to be clear, and relativity does also mess with lengths, but it does not change lengths that are perpendicular to the motion, and it does not change distances travelled. Please consider the light clock an example that is not, as written, a watertight derivation.

It’s not really a paradox, because in order for the person on the ground and the person on the train to compare their clocks over a period of time, they’ll have to meet each other twice, and that means at least one of them will have to accelerate; for example, the train might reverse in order to go back to where it started. The symmetry that we wanted to conserve only applies to constant motion. Once acceleration enters the picture, we can distinguish between something that has accelerated and something that has not; time dilation will be measured as happening to the object whose speed has changed.

Okay, fine, I guess it is convenient that the speed of light is a constant. Convenient for defining units, anyway. We use light for defining the metre, as well as the second!

Carus quite openly has some confusing translation choices for the word Anschauung. There might be better translations, but the public domain is so convenient. Moreover, in some ways it can be easier to put the pieces together when the seams are visible.

Kant uses the term “completion”—which is, I’m pretty sure, intended as mathematical terminology, as in, “the real numbers are the completion of the rational numbers.” Mind you, given that he also talks about extending things to infinity, I do wonder if “compactification” might not be a more accurate analogy. (Did the distinction between completion and compactification exist at that time? Bernard Bolzano was two years old and had definitely not yet given his explicit formulation of the Axiom of Completeness, so I would guess not. As I understand it, Bolzano was formalizing some existing ideas…)

Update: My understanding is a little bit anachronistic. See John Encaustum’s helpful comment below.

For those not in the know, completion of a space is a process whereby we ensure that any sequence that gets closer and closer together must tend toward a limit point that is also in the space. Notably, on any subset of the usual real line, “completion” of this sort will require the inclusion of all finite boundary points. In different places, Kant refers both to series and to limits in ways that seem to reference ideas like this. (For example: “In mathematics and in natural philosophy human reason admits of limits, but not of bounds, viz., that something indeed lies without it, at which it can never arrive, but not that it will at any point find completion in its internal progress.”)

Compactification is stronger than completion. In a compact space, every sequence has a convergent subsequence, whether its elements are getting closer together or not. Bounded intervals in the real line that include their endpoints are always compact in this sense. Unbounded intervals—those that extend to infinity in one or the other direction or indeed both—are generally not compact. You can, however, compactify them by adding a point at infinity (or perhaps one at each end) for the unbounded sequences to be converging to.

Compactification of this type sounds convenient, right up until somebody asks “Okay, then, what is zero times infinity?” At which point, it becomes necessary to explain that the compactification is just about the sequences and multiplication is not necessarily included. Honestly, the metaphysical analogies almost write themselves…

My thanks to John Psmith for noting this in his philosophically thought-provoking review of Einstein’s Unification.

A fun read! Someday I will have to bite a bullet and discuss Kant’s claims re a priori geometry at length but for now I don’t want to contradict anything. On footnote 9 re completeness and compactification, my guess has been it’s the completion of series or sequences by their asymptotic limits he has in mind - completion as in “completed infinity” that had been a central concept in the Scholastics’ work on infinite sequences and series, as in Oresme, that thereby became central to Leibniz’s intensive quantity and calculus work, thus also crucial for Kant as a successor to Wolff. A crucial precursor for both modern compactness and modern completeness rather than a great match for either.

The part about Galileo is great and the connection with Kant and metaphysics is great. I never was attracted to metaphysics. As an science major I always liked ontology better because it seemed more relevant to science. I definitely will read Kant now!